I think i am confused in how to use Melodic scales .

can we use Harmonic and Melodic Scales of a key at the same time?

for example build chord stabs with Harmonic Scales and a lead line with Melodic ?

and if yes . can u give us a good example? because as much as i tried to use Melodic keys over Harmonic scales . it sounds very dissonant .

help would be appreciated

thanks

[quote]alinenunez (11/04/2011)[hr]I think i am confused in how to use Melodic scales .

can we use Harmonic and Melodic Scales of a key at the same time?

for example build chord stabs with Harmonic Scales and a lead line with Melodic ?

and if yes . can u give us a good example? because as much as i tried to use Melodic keys over Harmonic scales . it sounds very dissonant .

help would be appreciated

thanks[/quote]

Well it depends on the Melodic line…but let’s say you do an ascending major scale as a melody. If you held the root down an octave higher (say C2 in a C major scale) then all the notes except the B would work. However, if you move the harmony up a fifth then all the notes in the major scale would fit. Also going down a 4th is pretty much the same as going up a 5th (meaning it ends up being G in the C scale), but it gives a different feel depending on which overall direction the line of the melody is moving. Sometimes having a harmony move opposite from a melodic line gives it more interest.

One last thing is that the harmony doesn’t have to move note-for-note with the melody. In fact, the more it hangs on, the more chance it has to show off its overtones and act like a harmony (unless you’re in a Barbershop quartet) ![]()

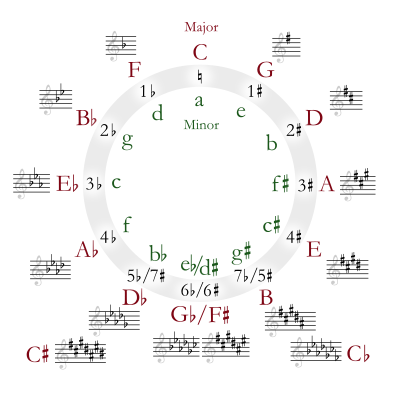

Im no theory expert, however think of it this way. The difference is one semitone. Play any two notes that are one ST apart and see what you get… dissonance. I would pick one and stick to it. You can always use the circle of fifths to make a quick change if need be.

I really hope SA give us some really in depth music theory tutorial vids soon, its so frickin confusing ![]()

[quote]howiegroove (12/04/2011)[hr]Im no theory expert, however think of it this way. The difference is one semitone. Play any two notes that are one ST apart and see what you get… dissonance. I would pick one and stick to it. You can always use the circle of fifths to make a quick change if need be.[/quote]

Yes, that’s true, semitones do sound dissonant (which is technically why B & C played at the same time don’t sound nice). However it gets more complicated–it also depends on the direction of the melodic line, how long you stay on the semitone, and moving a semitone up/down an octave.

For example if your melody is a repetition of three descending notes (C-B-G) with a held C bass (an octave lower), the B doesn’t come across so dissonant. Why? because it’s being couched by a repeating C and G on each side whose harmonics are reinforcing the C in the bass line. In classical music a repetition like this is called an Ostinato and sometimes musicians play with the lengths of the notes as they repeat them – to me this is similar to what you hear in Progressive melodic lines that change after 4 bars.

Another thing to consider is whether the stab already has a harmonic chord in it–some stabs do and those harmonics can also clash with the melody. If so you might want to choose a different stab, or try and re-create the stab by separating the chord onto different tracks–and then use automation to buff out the clash.

I guess my point is, don’t be afraid of semitones – there are ways to work with them to make your music more interesting.

[quote]howiegroove (12/04/2011)[hr]…You can always use the circle of fifths to make a quick change if need be.[/quote]

BTW, the circle of fifths really isn’t too complicated. There’s a great short article about it on Wikipedia (especially the section halfway down “in lay terms”):

[url]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circle_of_fifths[/url]

So basically what they are saying is that if you start on a note (like C) and go up a fifth (like G - which is 7 white & black keys or semitones) and then go up a fifth again (which is D) that is equivalent to wrapping back around on the scale and going up a whole step (two black & white keys or semintones). So the circle is kinda like walking a latter–go up a fifth, go down a fourth, up a fifth, down a fourth, etc. Also every major key (like C) has a twin minor key (like A) which walk the exact same notes but start a third down (or 3 white & black keys or semintones down).

So you can see what chords fit well together in a chord progression because of how close they are to each other on the circle. E.G. C maj, G maj, F maj & A min work well together. Make sense?

Personally i was a total fail at music theory… I think it more important to just practice playing keyboards.

Learn a few songs/work out some riffs you like and you will start to get a natural picture of chord progressions etc.

I tend to start all my tracks of in Cmin scale as its the only one i really know… once ive a riff sorted i play a bass in… then transpose everything until the bass is in the right register for ultimate phatness.

I totally agree that playing has been more valuable than theory–but a little bit of theory gave me some new ideas to play with.

I liked your idea of writing in an easy key (like C-minor) and then transposing–though you’ll notice that certain keys sound stronger than others. This is because of the physics of sound waves…middle C is at 220 Hz and has nice even numbers when it doubles (like 440, etc)…this means it has more overtones that aren’t canceling each other out. When you transpose it may sound less epic w/o some mixing aid. In fact another strong minor key to experiment with is G-minor (which is a fifth higher ;-).

Nice tips . thanks ![]()

[quote]lattetown (14/04/2011)[hr]…This is because of the physics of sound waves…middle C is at 220 Hz and has nice even numbers when it doubles (like 440, etc)…this means it has more overtones that aren’t canceling each other out…[/quote]

You know, I should always be careful when talking about the physics of music. Actually A is at 220hz, not C. And, it turns out the ratios between the frequencies are the important part of what makes them sound strong.

[quote]…When two frequencies are near to a simple fraction, but not exact, the composite wave cycles slowly enough to hear the cancellation of the waves as a steady pulsing instead of a tone. This is called beating, and is considered to be unpleasant, or dissonant…

[url]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Physics_of_music[/url]

[/quote]

I’m going to have to strongly disagree with the idea that there is anything more valuable than knowledge of musical theory. This is like saying, “eh, I never understood grammar and punctuation, but I’m going to write a novel anyway.” I have students that come into the program here who can play very well, but their knowledge is so limited to just a few chords in the blues progression (I, IV and V). Sorry, but I feel that if you don’t know how to speak this language, you’re going to miss a LOT of musical options when the writer’s block hits. Ok, now that I’ve said that, perhaps I can help a bit.

First, I’m a bit concerned with the terminology being used in the thread here. Latte… what exactly do you mean by using scales that are “harmonic” or “melodic”? Are you referring to the types of minor scales one can use by altering the 3, 6 and 7 scale degrees from the “natural” variety?

Second, what is a “harmonic chord”? Are you talking about the harmonics opened above in the overtone series? I’m not sure what is being inferred here.

Fill me in so I can help further…

Be careful of this concept as well, because in our present tuning system of equal temperament, the low and high registers are stretched just a bit so that everything from bottom to top is kept in tune. If you tried tuning A3 to exactly the frequency 220Hz, it would be sound sharp. This phenomena is odd, I know, because the tones are purposely pushed out of tune, but for some reason the ear perceives that as more “uniform” across the pitch spectrum.

Ever notice that it is hard to tune your bass and your high ends, like hats and shakers? It’s because your westernized ear is too used to equal temperament, and Ableton, Logic, Cubase, whatever, does NOT by default stretch the tuning. This is why your tunes might not sound quite right, no matter what you do to fix it.

Jamie

[quote]lattetown (30/04/2011)[hr][quote]lattetown (14/04/2011)[hr]…This is because of the physics of sound waves…middle C is at 220 Hz and has nice even numbers when it doubles (like 440, etc)…this means it has more overtones that aren’t canceling each other out…[/quote]

You know, I should always be careful when talking about the physics of music. Actually A is at 220hz, not C. And, it turns out the ratios between the frequencies are the important part of what makes them sound strong.

[quote]…When two frequencies are near to a simple fraction, but not exact, the composite wave cycles slowly enough to hear the cancellation of the waves as a steady pulsing instead of a tone. This is called beating, and is considered to be unpleasant, or dissonant…

[url]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Physics_of_music[/url]

[/quote]

[/quote]

[quote]JamieinNC (30/04/2011)[hr]Be careful of this concept as well, because in our present tuning system of equal temperament, the low and high registers are stretched just a bit so that everything from bottom to top is kept in tune. If you tried tuning A3 to exactly the frequency 220Hz, it would be sound sharp. This phenomena is odd, I know, because the tones are purposely pushed out of tune, but for some reason the ear perceives that as more “uniform” across the pitch spectrum.

Ever notice that it is hard to tune your bass and your high ends, like hats and shakers? It’s because your westernized ear is too used to equal temperament, and Ableton, Logic, Cubase, whatever, does NOT by default stretch the tuning. This is why your tunes might not sound quite right, no matter what you do to fix it.

Jamie

[quote]lattetown (30/04/2011)[hr][quote]lattetown (14/04/2011)[hr]…This is because of the physics of sound waves…middle C is at 220 Hz and has nice even numbers when it doubles (like 440, etc)…this means it has more overtones that aren’t canceling each other out…[/quote]

You know, I should always be careful when talking about the physics of music. Actually A is at 220hz, not C. And, it turns out the ratios between the frequencies are the important part of what makes them sound strong.

[quote]…When two frequencies are near to a simple fraction, but not exact, the composite wave cycles slowly enough to hear the cancellation of the waves as a steady pulsing instead of a tone. This is called beating, and is considered to be unpleasant, or dissonant…

[url]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Physics_of_music[/url]

[/quote]

[/quote][/quote]

Nice tip Jamie !!! Thank

what i was saying is that if i build a song based in harmonic chords. why it sounds so dissonant to layer down a lead line in Melodic scale .

[quote]JamieinNC (30/04/2011)[hr]I’m going to have to strongly disagree with the idea that there is anything more valuable than knowledge of musical theory…First, I’m a bit concerned with the terminology being used in the thread here. Latte… what exactly do you mean by using scales that are “harmonic” or “melodic”? Are you referring to the types of minor scales one can use by altering the 3, 6 and 7 scale degrees from the “natural” variety?

Second, what is a “harmonic chord”? Are you talking about the harmonics opened above in the overtone series? I’m not sure what is being inferred here.

Fill me in so I can help further…[/quote]

Hey Jamie, while I agree that music theory gives you tools to explore music in new ways, I don’t agree that having academic precision of terminology is necessary for artists to make great art–to further your analogy, most of today’s best selling writers are not degreed from University English departments (ironic, really).

Instead of saying something with music, it’s just as easy to get distracted by the science and tradition of musical theory as much as it is to get caught up with the right technology to own or how to layer kicks exactly like another artist. In the end, the kind of music created on SA is about how well it communicates with the audience.

Not sure I used the word “harmonic scale”, but when I was talking about the circle of fifths before (and why C-major sounds stronger in western music which is what we’re doing here on SA), I mean that each note has a resonance that is complimented in a harmony. The physics of harmony that’s important pragmatically when chucking tracks together is the overtones a sample or LFO makes (i.e. its timbre). For example, the natural harmonics of brass sounds reinforce 5ths and 4ths, while strings emphasize 3rds and 6ths. [url]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timbre[/url]

I think when you’re talking about “Harmonic Chords” you mean how chords lead to a resolution in a chord progression…which can be very helpful in dance music. [url]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chord_progression[/url]

As far as equal temperament, that is very academic and probably most of us can create dance tracks without worrying about it, but there is something interesting about modulated electronic sounds–they are different than traditional instruments because it’s like playing a guitar while stretching the strings on such a micro-managed scale that you get a new sound. That said, most popular music is not going to be written in 12-tone…if you want your dance track to be well received just use your ears in the end to see if the theory helps your piece or is getting in the way. ![]() [url]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equal_temperament[/url]

[url]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equal_temperament[/url]

One last thought, when I hear someone say “be careful” or “I’m concerned” about how you approach music, I would take that with a grain of salt.

In fact, I would say the opposite–don’t be careful! Experiment as much as you want–what’s the worst that could happen? You’re not going to die if two notes clash–in fact, you may have come up with a sound that works for a different venue–like in an Indy film soundtrack.

There will always be critics and gurus in the world, but unless they are footing the bill, you get to decide whether you use the advice or ignore it.

[quote]Hey Jamie, while I agree that music theory gives you tools to explore music in new ways, I don’t agree that having academic precision of terminology is necessary for artists to make great art–to further your analogy, most of today’s best selling writers are not degreed from University English departments (ironic, really).[/quote]

I’m not talking about accuracy of terminology. I’m addressing the actual concept itself. The thing we forget is that there are going to be people who are simply “instinct” driven, those who know what to do without being able to explain why they do it this way or that. To be quite honest, if any of us here were able to do that, we probably wouldn’t be here. We would be on the global circuit already performing to thousands, perhaps millions of people. For the rest of us mortals, it takes a bit more knowledge and understanding of the language get to that point. That is where theory is going to come in. I believe that if you aren’t granted a prodigal musical instinct, arm yourself with sufficient knowledge to make up for that void. Of course, work your rear-end off, too.

[quote]Instead of saying something with music, it’s just as easy to get distracted by the science and tradition of musical theory as much as it is to get caught up with the right technology to own or how to layer kicks exactly like another artist. In the end, the kind of music created on SA is about how well it communicates with the audience.[/quote]

You are absolutely correct! There are TONS of overwhelming factors that each one of us face when we open a new live set or put a kick sound into a new sampler. Some might spend too much time worrying about this sound or that knob, that melody or this chord…My point is that one arrives at the finished product in one of two ways, additive or subtractive.

The additive measure is usually one where there is no knowledge or decision making made prior to experimentation. In other words, whatever happens, happens. I’ll know if it sounds good when I hear it. This might work for some people, but it can be potentially long-term and mentally taxing due to the relatively haphazard way of arriving at some result. Some might not even be able to reach any useable material, throwing hands up in dismay and becoming frustrated.

Then there is the subtractive method, where an individual has a lot of knowledge going into a project about what they want with regards to sounds or scales/harmonies. With a wealth of possibility there, the person actually makes decisions about what they want to do and begins work from there, gradually reaching a specific, contrived goal by eliminating sounds, melodies or chords that don’t work toward that end-result.

To me, I would much rather make rather pointed decisions about what I would like to do musically so I have some light at the tunnel, as opposed to leaving an unknown end result to “chance” or random “noodling” about with notes and chords with the hopes something along the line is going to work.

Say, for instance, I start working on a tune. I say to myself, “I want to write a dark tune that is slightly melodic with a couple of chords and a really distorted, overdriven, mechanical bass and drum foundation.” That is specific, but not so specific yet that the tune is “cast in stone.” Now, if I start focusing on the “dark” melody/harmony idea, I might get more specific and say to myself, “Knowing that the phrygian mode is a pretty dark-sounding scale, I’m going to establish that first. I’ll build the scale, and listen to it being played to get a feel for the emotional quality of the tones.”

Then I might go on to decide that I don’t want to be as dark with the chords, since the melody itself will be dark, because I believe that music is about contrast. So…“maybe I’ll go with a lighter mode with the chords, like Dorian mode, layer them up with the scale and play each chord from the Dorian mode along side the looping scale and hear what happens.”

Then, I find a chord progression that sounds good against the looping scale. The chords sound as if they are rising, or going up in pitch, perhaps. Then perhaps…“with the melody I might have a predominance of leaps downward, using two or three notes from the scale…” And on, and on, and on…

I just think that setting a goal, and using your knowledge to reach that end (good or bad) is much more efficient and style-setting than having great hope that your tweaking and note choice will produce something wonderful. Each person will eventually reach the end result, but the knowledgeable, decision-making person will get there faster, with a greater retention of what they did to get there in the first place. Like I said, if your skills are so good that theory isn’t an issue, you’d already be on the stage. I don’t think anyone on this forum can deny that. And if you aren’t interested in theory, you are essentially going to learn only as much about chords, rhythms and melodies as Prydz, Hawtin, Villalobos, Beyer, and Van Buuren feel like teaching you through their songs.

[quote]Not sure I used the word “harmonic scale”, but when I was talking about the circle of fifths before (and why C-major sounds stronger in western music which is what we’re doing here on SA), I mean that each note has a resonance that is complimented in a harmony. The physics of harmony that’s important pragmatically when chucking tracks together is the overtones a sample or LFO makes (i.e. its timbre). For example, the natural harmonics of brass sounds reinforce 5ths and 4ths, while strings emphasize 3rds and 6ths. [url]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timbre[/url]

I think when you’re talking about “Harmonic Chords” you mean how chords lead to a resolution in a chord progression…which can be very helpful in dance music. [url]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chord_progression[/url][/quote]

Each note has a multitude of chords of which it could be a member. This is why equal temperament (below) is such an important concept to remember when building chord progressions or stacked timbres electronically. I refer you to the request on the board to Phil regarding how to make sampled orchestras sound better in a DAW. Anyone ever stop to ask themselves why that might be one of the most difficult (if not impossible) things ever for an electronic musician?

[quote]As far as equal temperament, that is very academic and probably most of us can create dance tracks without worrying about it[/quote]

Sorry, but this statement maintains the argument I have about NOT having as much knowledge about the craft as you possibly can have, and addressing it to perhaps see if it makes your music sound better. The computer does not know equal temperament unless you spend the time making the computer fabricate it, but this is beside the point I’m trying to make. What I’m trying to say in this lengthy response is that very important musical concepts that are placed out of sight and out of mind because they might not APPEAR to be important, or are deemed to difficult to deal with, are doing a great disservice to you and your music. Everyone wants to fiddle about with knobs and samples and notes without taking the time to understand just a few basic musical concepts that MIGHT MATTER.

I’m not saying everyone should become a music theory academic, but I am saying a little bit of awareness goes a long way. Could be the one thing that makes you stand out in a SEA of people with a computer and a DAW.

J

[quote]JamieinNC (30/04/2011)[hr]The thing we forget is that there are going to be people who are simply “instinct” driven, those who know what to do without being able to explain why they do it this way or that. To be quite honest, if any of us here were able to do that, we probably wouldn’t be here.[/quote]

Not sure I agree with that–you can develop your “instincts” through experimenting and playing just as much as you can develop your cerebral understanding of music through studying theory.

[quote]We would be on the global circuit already performing to thousands, perhaps millions of people. For the rest of us mortals, it takes a bit more knowledge and understanding of the language get to that point. That is where theory is going to come in. I believe that if you aren’t granted a prodigal musical instinct, arm yourself with sufficient knowledge to make up for that void. Of course, work your rear-end off, too.[/quote]

Having sung the Mozart Requiem with the Seattle Symphony under Itzak Perlman, I can tell you that there are many talented people in the world of music that aren’t on the global stage even though they have the “instincts” and the “knowledge”.

[quote]My point is that one arrives at the finished product in one of two ways, additive or subtractive.

The additive measure is usually one where there is no knowledge or decision making made prior to experimentation. In other words, whatever happens, happens. I’ll know if it sounds good when I hear it. This might work for some people, but it can be potentially long-term and mentally taxing due to the relatively haphazard way of arriving at some result. Some might not even be able to reach any useable material, throwing hands up in dismay and becoming frustrated.

Then there is the subtractive method, where an individual has a lot of knowledge going into a project about what they want with regards to sounds or scales/harmonies. With a wealth of possibility there, the person actually makes decisions about what they want to do and begins work from there, gradually reaching a specific, contrived goal by eliminating sounds, melodies or chords that don’t work toward that end-result.[/quote]

I thinks that’s an straw man argument–there are not only two ways to create music–it’s rarely either “all planned out” or “all inspired”. The best works probably are both. The subtractive ones probably sound rigid and derivative.

To me this is the same argument that happened in classical music when musical expression was modeled after a “classical” well balanced sonata form and then a generation later everyone rebelled and wanted a freer “romantic” form.

But, that said, if this works for you personally–then by all means don’t stop using that process because someone else doesn’t like it

[quote]…“Knowing that the phrygian mode is a pretty dark-sounding scale, I’m going to establish that first. I’ll build the scale, and listen to it being played to get a feel for the emotional quality of the tones.”

Then I might go on to decide that I don’t want to be as dark with the chords, since the melody itself will be dark, because I believe that music is about contrast. So…“maybe I’ll go with a lighter mode with the chords, like Dorian mode, layer them up with the scale and play each chord from the Dorian mode along side the looping scale and hear what happens.” [/quote]

LOL, I bet the number of DJs and Electronica producers that say “you know I believe that mix needs a little Ionian mode” including yourself is countable on one finger. :-p

(nice reference to ancient greek music though)

[url]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musical_mode[/url]

[quote]I refer you to the request on the board to Phil regarding how to make sampled orchestras sound better in a DAW. Anyone ever stop to ask themselves why that might be one of the most difficult (if not impossible) things ever for an electronic musician?[/quote]

This is a philosophical difference I guess…to me what’s interesting about Electronica is the new timbre that are possible, not simulating an existing instrument. Commercial projects still use real studio musicians for orchestral parts and vocals.

[quote]The computer does not know equal temperament unless you spend the time making the computer fabricate it[/quote]

Well, not quite true…here’s a link to Ableton’s forum about this:

[url]not equal-tempered, just intonation & Live? - Ableton Forum

You’ll see from the first post that Ableton uses equally tempered by default and everyone talks about using plugins to get a different tuning.

If the person using intuition had never experienced a musical idea, it would be interesting to see what they would do. I would argue that for instinct alone, it would be a longer, more tasking process to achieve a musical idea considered “acceptable” by the public. You said it yourself…it’s all about communicating with your audience. So this leads me to the point that everyone uses music theory to some degree, whether it be by ear or study. When you get it by ear, you really are at the mercy of whomever it is you listen to on a regular basis. When you study it, you enable yourself to piece it together in new and fresh ways. Else, you run the risk of alienating your audience with chords, melodies, rhythms, textures, timbres that aren’t exactly pleasant.

I’m pretty sure every person in the Seattle Symphony has studied music theory and could explain almost every concept used in the pieces they play. Now if you’re Pavarotti, who couldn’t read a note of music, that’s a different story. But not everyone can be Pavarotti, can they? (Tell me the Lachrymosa is not the most beautiful thing ever…)

Mozart improvised. Beethoven Planned. Beethoven is hardly “rigid” or “derivative” sounding. In fact, the transition to Romantic musical ideals only happened because Beethoven pushed musical limits further than any individual in history. His truly reclusive nature, still steeped in Bach and Haydn mind you!, became so abstract and forward looking that it took the Philistine Franz Liszt 50 years later to play the Hammerklavier…No one could play it, much less understand it. It wasn’t a desire to seek something else, the Romantic Period. No one had a choice, because everyone though Beethoven had achieved everything that could be achieved! Chopin, Schumann, Liszt and Brahms had to act fast…

And to boot, Prokoffiev wrote fabulous, Beethoven-inspired Sonatas as late as 1950, so the idea that forms and styles become archaic is starting to become a dated and rather inaccurate view of musical style and progression. It really is all very cyclical.

I didn’t say DJs and producers sit in their studios and talk to themselves in strange tongues. Are you sure they don’t? Haha… They certainly have a tendency to surround themselves with musical talent in jazz and classical training, I can assure you of that… Funny that the Ancient Greek system of tones and musical gravity are still used a few thousand years later!

That’s interesting about Ableton using the tempered scale. I’m going to look into that. I was pretty sure the Hz values were static.

J

Just want to say that I’m not trying to be aggressive, I just like stimulating debate. I’m very friendly and don’t like or dislike Latte any less that if he agreed with everything I said!

Just want to throw that out there as a disclaimer!

[quote]JamieinNC (30/04/2011)[hr]Just want to say that I’m not trying to be aggressive, I just like stimulating debate. I’m very friendly and don’t like or dislike Latte any less that if he agreed with everything I said!

Just want to throw that out there as a disclaimer![/quote]

Ditto! ![]()

my name is Jer, btw